A MUSEUM FOR YOUNG GENTLEMEN AND LADIES

15th Edition - ca. 1799

Transcriber's Notes:

- Each page repeats the first word of the next page at the bottom

right - this has not been reproduced in this text version.

- As can be seen on this page, the book uses the long 's' (ſ) in

non-final positions - this has not been reproduced in this text

version, as it would make the text less easily searchable. A

non-final

double 's' is sometimes written with two long 's's, and sometimes with

a long 's' followed by a short (or final) 's' (somewhat like the

ß of German).

- 'st' and 'ct' are usually written with a ligature - this has not

been preserved in the text; 'ae' and 'oe' ligatures

have been preserved, however.

- Colons, semicolons, question marks, and brackets are usually

surrounded by spaces - in this

text, the modern convention has been followed.

- The book consistently uses '&c.' where we today use 'etc.' -

this has been preserved.

- The dimensions of the book are approx. 13½ cm. by 9 cm.,

so each line contains 8-9 words on average. This means that the

layout of the

following text does not usually match that of the book.

- Compound words like "every body" are often written with a space

in the middle - this has been preserved where it appears.

- Page numbers have been omitted.

- '[sic]' has been inserted at many places in the text to let the

reader know that the preceding word or phrase appeared as such in the

original. These appear in blue in the HTML version.

- A number of names are spelled differently from present-day usage,

e.g. Anna Bullen (Anne Boleyn) - in most cases, these have not been

marked.

- On one page, a letter is corrupted, and on the following line

letters appear to be missing - these have been marked with a comment in

square brackets.

- One major point of confusion should be mentioned: In the

section on the Seven Wonders of the World, what is usually described as

the Lighthouse of Pharos (shown in the woodcut) appears to have been

merged with the so-called Egyptian Labyrinth (described by Herodotus) -

see the title and the description in the text. In the next

section (the Pyramids of Egypt), there is a reference to a black marble

head on the third pyramid - perhaps this represents some confusion with

the Sphynx.

Front

Page, Obverse and Owner's Handwriting:

Image 1 Image 2 Image 3

A

MUSEUM

FOR

YOUNG GENTLEMEN

AND LADIES

OR A

FOR LITTLE

MASTERS AND

MISSES.

Containing

a Variety of

uſeful Subjects;

AND, IN

PARTICULAR,

With Letters, Tales and Fables, for

amuſement

and

Inſtruction.

ILLUSTRATED

WITH CUTS.

THE FIFTEENTH

EDITION,

WITH CONSIDERABLE ADDITIONS AND ALTERATIONS.

Printed

for DARTON and HARVEY,

Gracechurch-ſtreet, CROSBY and LETTERMAN, Stationers-Court, and

E. NEWBERY, St. Paul's Church-yard; and B.C. COLLINS,

Saliſbury.

[Reverse

of title page]

Printed by B.C. COLLINS, Canal,

Saliſbury.

MUSEUM

FOR

YOUNG GENTLEMEN AND LADIES.

NOTES AND POINTS

USED IN

Writing and Printing.

Before I begin to lay down rules for

reading, it will be necessary to take notice of the several points or

marks used in printing or writing, for resting or stopping the voice,

which are four in number, called

1. The Comma

(,)

|

3. Colon

(:) |

| 2. Semicolon

(;) |

4.

Period (.) |

These points are to give a proper time for breathing when you read, and

to prevent confusion of sense in joining words together in a sentence.

The Comma stops the reader's

voice till he can tell one,

and divides the lesser parts of a sentence. The Semicolon divides the greater parts

of a sentence, and requires the reader to pause while he can count two.

The Colon is used where the

sense is

complete, and not the sentence, and rests the voice of the reader till

he can count three.

The Period is put when the

sentence is ended, and requires a pause while he can tell four.

But we must here remark, that the Colon

and Semicolon are frequently

used promiscuously, especially in our bibles.

There are two other points, which may be called marks of affection; the

one of which is termed an Interrogation,

which signifies a question being asked, and expressed thus (?); the

other called an Admiration or

Exclamation, and marked thus

(!). These two points require a pause as long as a period.

We have twelve other marks to be met with in reading, namely,

1. Apostrophe

(’)

|

7.

Section (§

)

|

2.

Hyphen (-)

|

8. Ellipsis

(―)

|

3. Parenthesis ( )

|

9. Index

( ) )

|

4.

Brackets [ ]

|

10. Asterisk (*)

|

5. Paragraph

(¶ )

|

11.

Obelisk (†)

|

6.

Quotation (“)

|

12.

Caret (^)

|

Apostrophe is set over a word

where some letter is wanting, as in lov'd.

Hyphen joins syllables and

words together, as in pan-cake.

Parenthesis includes something

not necessary to the sense, as, I

know that in me (that is in my flesh) liveth, &c. Brackets include a word or words

mentioned as a matter of discourse, as, The little word [man] makes a great noise, &c.

They are also used to enclose a cited sentence, or what is to be

explained, and sometimes the explanation itself. Brackets and Parenthesis are

often used for each other

without distinction. Paragraph

is chiefly used in the bible, and denotes the beginning of a new

subject. Quotation is

used to distinguish what is taken from an author in his own

words. Section shews

the division of a chapter. Ellipsis

is used when part of a word or sentence is omitted, as p―ce. Index denotes some remarkable

passage. Asterisk

refers to some note in the margin, or remarks at the bottom of the

page; and when many stand together, thus ***, they imply that

something is wanting, or not fit to be read, in the author. The Obelisk or Dagger, and also parallel lines

marked thus (||), refer to something in the margin. The Caret, marked thus (^), is made use

of in writing, when any line or word is left out, and wrote over where

it is to come in, as thus,

had

A certain man two sons:

^ |

Here the word had was left

out, wrote over, and

marked by the Caret where to

come in.

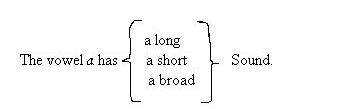

It may also in this place be proper to

mention the crooked lines or Braces,

which couple two or three

words or lines together that tend to the same thing; for

instance,

This is often used in poetry, where

three lines have the same rhyme.

The other marks relate to single words, as Dialysis or Diæresis, placed over vowels

to

shew they must be pronounced in distinct syllables, as Raphaël. The Circumflex is set over a vowel to

carry a long sound, as Euphrâtes.

An Accent is marked thus

(á), to shew where the emphasis must be placed, as negléct; or to

shew that the consonant following must be pronounced double, as hómage. To these

may be added the long ( ¯) and short ( ˘) marks, which denote the

quantity of syllables, as wātĕr.

RULES

FOR READING.

When you have gained a perfect knowledge

of the sounds of the letters, never guess at a word on sight, lest you

get a habit of reading falsely. Pronounce every word

distinctly. Let the tone of your voice be the same in reading as

in speaking. Never read in a hurry, lest you learn to

stammer. Read no louder than to be heard by those about

you. Observe to make your pauses regular, and make not any

where the sense will admit of none. Suit your voice to the

subject. Be attentive to those who read well, and remember to

imitate their pronunciation. Read often before good judges,

and thank them for

correcting you. Consider well the place of emphasis, and

pronounce it accordingly: For the stress of voice is the same

with regard to sentences as in words. The emphasis or force of

voice is for the most part laid upon the accented syllable; but if

there is a particular opposition between two words in a sentence, one

whereof differs from the other in parts, the accent must be removed

from its place: for instance, The

sun shines upon the just and upon the unjust. Here the

emphasis is laid upon the first syllable in unjust, because it is opposed to just in the same sentence, without

which opposition it would lie in its proper place, that is, on the last

syllable, as we must not imitate the

unjust practices of others.

The general rule for knowing which is the emphatical word in a

sentence, is, to consider the design

of the whole; for particular directions cannot be easily given,

excepting only where words evidently oppose one another in a sentence,

and those are always emphatical.

So frequently is the word that asks a question, as, who, what, when, &c. but not always.

Nor must the emphasis be always laid upon the same words in the same

sentence, but varied according to the principal meaning of the

speaker. Thus, suppose I enquire, Did my father walk abroad yesterday?

If I lay the emphasis on the word father,

it is evident I want to know whether it was he,

or somebody else. If I lay it upon walk, the person I speak to will

know, that I want to be informed whether he went on foot or rode on horseback. If I put the

emphasis upon yesterday, it

denotes, that I am satisfied that my father went abroad, and on foot,

though I want to be informed whether it was yesterday, or some time before.

RULES

TO READ VERSE.

There are two ways of writing on a subject, namely, in prose and verse. Prose is the common way of writing,

without being confined to a certain number of syllables, or having the

trouble of disposing of the words in any particular form. Verse requires words to be ranged

so, as the accents may naturally fall on particular syllables, and make

a sort of harmony to the ear: This is termed metre or measure, to which rhyme is

generally added, that is, to make two or more verses, near to each

other, and with the same sound; but this practice is not absolutely

necessary; for that which has no rhyme is called blank verse.

In metre the words must be so disposed, as that the accent may fall on

every second, fourth, and sixth syllable, and also on the eighth, tenth, and twelfth, if the lines run to that

length. The following verse of ten syllables may serve for an

example:

The

mónarch spóke, and stráit a múrmur

róse.

But English

poetry allows of frequent variations from this rule, especially in the

first and second syllables in the line, as in the verse which rhymes

with the former, where the accent is laid upon the first syllable.

Lóud

as the súrges, whén the témpest blóws.

But there are two sorts of metre, which

vary from this rule; one of which is when the verse contains but seven

syllables, and the accent lies upon the first, third, fifth, and seventh, as below:

Cóuld

we, whích we

néver cán,

Strétch our

líves beyónd their spán;

Beáuty líke a

shádow flíes,

Ánd our yóuth

befóre us díes. |

The other sort has a hasty sound, and

requires an accent upon every third syllable; as,

'Tis the vóice of the

slúggard,

I heár him compláin,

You have

wák'd me too soón, I must slúmber

agáin. |

You must always observe to pronounce a verse as you do prose, giving

each word and syllable its natural accent, with these two

restrictions: First, If

there is no point at the end of the line, make a short pause before you

begin the next. Secondly,

If any word in a line has two sounds, give it that which agrees

best with the rhyme and

metre; for example the word glittering

must sometimes be pronounced as of three syllables, and sometimes glitt'ring, as of two.

The

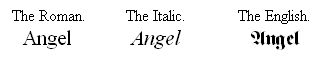

USE of CAPITALS, and the different LETTERS used in PRINTING.

The names of the letters made use of in printed books are distinguished

thus: The round, full, and upright, are called Roman; the long, leaning,

narrow letters are called Italic;

and the ancient black character is called English.

You have a specimen as

follows, viz.

The Old English is seldom

used but in acts of parliament, proclamations, &c. The Roman is chiefly in vogue for books

and pamphlets, intermixed with Italic,

to distinguish proper names, chapters, arguments, words in any foreign

language, texts of scripture, citations from authors, speeches or

sayings of any person, emphatical words, and whatever is strongly

significant.

The use of capitals, or great letters, is to begin every name of the

Supreme Being, as God, Lord, Almighty, Father, Son, &c.

All proper names of men

and things, titles of distinction, as King, Duke, Lord, Knight, &c.

must also begin with a capital. So ought every book, chapter,

verse, paragraph, and sentence after a period. A saying, or

quotation from any author, should begin with a capital; as ought every

line in a poem. I and O, when they stand single, must always be

capitals; any words, particularly names or substantives, may begin with

a capital; but the common way of beginning every substantive with a

capital is not commendable, and is now much disused.

Capitals are likewise often used for ornament, as in the title of

books; and also to express numbers, and abbreviations.

A CONCISE

ACCOUNT OF ANCIENT BRITAIN.

CHAP. I.

ENGLAND

and Scotland, though but

one

island, are two kingdoms, viz. the kingdom of England and the kingdom

of Scotland; which two kingdoms being united, were in the reign of

James

I. called Great-Britain. The shape of it is triangular, as

thus  ,

and 'tis surrounded by the seas. Its utmost extent or length is

812 miles, its breadth is 320, and its circumference 1836; and it is

reckoned one of the finest islands in Europe. The whole

island was anciently called Albion, which seems to have been

softened from Alpion; because the word alp, in some of the original

western languages, generally signifies very high lands, or hills; as

this isle appears to those who approach it from the Continent. It

was likewise called Olbion, which in the Greek signifies happy; but of those times there is

no certainty in history, more than that it had the denomination, and

was very little known by the rest of the world.

,

and 'tis surrounded by the seas. Its utmost extent or length is

812 miles, its breadth is 320, and its circumference 1836; and it is

reckoned one of the finest islands in Europe. The whole

island was anciently called Albion, which seems to have been

softened from Alpion; because the word alp, in some of the original

western languages, generally signifies very high lands, or hills; as

this isle appears to those who approach it from the Continent. It

was likewise called Olbion, which in the Greek signifies happy; but of those times there is

no certainty in history, more than that it had the denomination, and

was very little known by the rest of the world.

The people that first lived in this island, according to the best

historians, were the Gauls, and afterwards the Britons. These

Britons were tall, well made, and yellow haired, and lived frequently a

hundred and twenty years, owing to their sobriety and temperance, and

the wholesomeness of the air. The use of clothes was scarce known

among them. Some of them that inhabited the

southern parts covered their nakedness with the skins of wild beasts

carelessly thrown over them, not so much to defend themselves against

the cold as to avoid giving offence to strangers that came to traffic

among them. By way of ornament they used to cut the shape of

flowers, and trees, and animals, on their skin, and afterwards painted

it of a sky colour, with the juice of woad, that

never wore out.

They lived in woods, in huts covered with skins, boughs, or

turfs. Their towns and villages were a confused parcel of huts,

placed at a little distance from each other, without any

order or distinction of streets. They were

generally in the middle of a wood, defended with ramparts, or mounds of

earth thrown up. Ten or a dozen of them, friends and brothers,

lived together, and had their wives in common. Their food was

milk and flesh got by hunting, their woods and plains being well

stocked with game. Fish and tame fowls, which they kept for

pleasure, they were forbid by their religion to eat.

The

chief commerce was with the the Phœnician merchants, who, after

the discovery of the island, exported every year great quantities of

tin, with which they drove a very gainful trade with distant nations.

In

this situation were the Ancient Britons when Julius Cæsar, the

first Emperor of Rome, and a great conqueror, formed a design of

invading their island, which the Britons hearing of, they endeavoured

to divert him from his purpose by sending ambassadors with offers of

obedience to him, which he refused, and in the 55th year before the

coming of our Saviour upon earth, he embarked in Gaul (that is France)

a great many soldiers on board eighty ships.

At his

arrival on the coast of Britain he saw the hills and cliffs that

ran out into the sea covered with troops, that could easily prevent his

landing, on which he sailed two leagues farther to a plain and open

shore, which the Britons perceiving sent their chariots and horse that

way,

whilst the rest of their army advanced to support them.

The largeness of Cæsar's vessels hindered them from coming near

the

shore, so that the Roman soldiers saw themselves under a necessity of

leaping into the sea, armed as they were, in order to attack their

enemies, who stood ready to receive them on the dry ground.

Cæsar perceiving that his soldiers did not exert their usual

bravery,

ordered some small ships to get as near the shore as possible, which

they did, and with their slings, engines, and arrows so pelted the

Britons, that their courage began to abate. But the Romans were

unwilling to throw themselves into the water, till one of the

standard-bearers leaped in first with his colours in his hand, crying

out aloud, Follow me, fellow

soldiers, unless you will betray the Roman Eagle into the hands of the

enemy. For my part I am resolved to discharge my duty to Caesar

and the Commonwealth. Whereupon all the soldiers followed

him, and began to fight. But their resolution was not able to

compel the Britons to give ground; nay, it was feared they would have

been repelled, had not Cæsar caused armed boats to supply them

with recruits, which made the enemy fall back a little. The

Romans improving this advantage advanced, and getting firm footing on

land, pressed the Britons so vigorously that they put them to the

rout. The Britons, astonished at the Roman valour, and fearing a

more obstinate resistance would but expose them to

greater mischiefs, sent to sue for peace and offer

hostages, which Cæsar accepted, and a peace was concluded four

days after their landing. Thus having given an account of Ancient

Britain, and Cæsar's invasion, we shall proceed to the History of

England, and the several Kings by whom it has been governed.

A COMPENDIOUS

HISTORY OF ENGLAND.

CHAP. II.

AS England was long governed by

Kings

who were natives of the country, so it may not be improper to

distinguish that tract of time by the name of the British Period.

Those Kings were afterwards subdued by the Romans, and the time that

warlike people retained their conquest we shall call the Roman

Period. When the Saxons brought this country under their

subjection, we shall denominate the time of their sway the Saxon

Period. Lastly, when the Danes invaded England, and conquered it,

we

shall term the series of years they possessed it the Danish Period.

This country was originally called Albion; but one Brutus, a Grecian

hero, having landed here about 1100 years

before Christ, changed the ancient name to

Britannia;

from which time, to the arrival of Julius Cæsar here, there had

reigned sixty-nine Kings, all natives of England.

In respect to the Roman Period we may observe, that Julius Cæsar

first landed in Britain from Gallia, and made it tributary to the

Romans; but soon after the birth of Christ the Emperor Claudius brought

this country entirely under his subjection, and the Emperor Adrian built

the long wall between

England and Scotland.

In the beginning of the second century the Christian religion was

planted in England; and in the fifth century the Britons, finding

themselves overpowered by the Scots, called over the Saxons to their

assistance, who were so charmed with the country that they determined

to continue here, and subdue it.

The most remarkable occurrences in the Saxon Period are, that such of

them who embarked for England had been particularly distinguished by

the name of Angles, and from them the name of Britannia was changed to

that of Anglia. The Saxons also divided the country among

themselves into seven kingdoms, known by the name of the Saxon

Heptarchy, viz. 1. Kent, 2. Essex, 3. Sussex, 4. Wessex, 5. East

Anglia, 6. Mercia, 7. Northumberland. But at length Wessex

over-powering

the rest, formed them all into one monarchy.

One of those West-Saxon Kings, called Ina, made many good laws, some of

which are still extant: he also was the first that granted Peter's

pence to the Pope.

In regard to the Danish Period we shall only remark, that the Danes had

for a long time acted as pirates or sea robbers upon the English

coasts, and made several incursions into the country, when their King

Canute

possessed himself of the crown of England; however their government did

not continue long.

Canute reigned eighteen years, and left three sons, Harold, Canute, and

Sueno; to the first he gave

England, to the second Denmark, and to the third Norway.

Harold reigned five years, and was succeeded by his half-brother

Hardi-Canute,

who died two years after, and with him ended the tyrannical government

of the Danes in England.

THE

INTERMEDIATE HISTORY OF ENGLAND.

CHAP. III.

WE shall divide this part of our history

into four periods;

1. The Kings of the Norman

Line; 2. Those of the House of Anjou; 3. Of the House of Lancaster; 4.

Of the House of York.

The

NORMAN

KINGS.

WILLIAM I. sirnamed [sic]

the Conqueror, gained a signal victory over King Harold, by which means

he procured the crown of England. This Prince was the son

of Robert, Duke of Normandy, by one of his mistresses called Harlotte,

from whom

some think the word harlot is derived; however, as this amour seems

odd, we shall entertain the reader with an account of it. The

Duke riding one day to take the air passed by a company of country

girls, who were dancing, and was so taken with the graceful carriage of

one of them, named Harlotte, a skinner's daughter, that he prevailed on

her to cohabit with him, and she was ten months after delivered of

William, who, having reigned 21 years, died at Rouen, in September,

1087.

WILLIAM II. sirnamed Rufus, succeeded his father; he built

Westminster-hall, rebuilt London-bridge, and made a new wall round the

Tower of London. In his time the sea overflowed a great part of

the estate belonging to Earl Goodwin, in Kent, which is at this day

called the Goodwin Sands. The King was killed accidentally by an

arrow in the New Forest, and left no issue. He reigned fourteen

years, and was buried in Winchester Cathedral.

HENRY I. youngest son of William the Conqueror, succeeded his brother

William II. in 1100. He reduced Normandy, and made his son Duke

thereof. This Prince died in Normandy of a surfeit, by eating

lampreys after hunting, having reigned 35 years.

STEPHEN, sirnamed of Blois, succeeded his uncle Henry I. in 1135; but

being continually harassed by the Scotch and Welsh, and having reigned

19 years in an uninterrupted series of troubles, he died at Dover in

1154, and was buried in the Abbey at Feversham, which he had erected

for the burial place of himself and family.

HENRY II. son of Geoffrey Plantagenet, Earl of Anjou, succeeded Stephen

in 1154. In him the Norman and Saxon blood was united, and with

him

began the race of the Plantagenets, which ended with Richard III.

In this King's reign Thomas à Becket, son to a tradesman in

London,

being made Lord High Chancellor, and

afterwards Archbishop of Canterbury, affected on

all occasions to oppose and to be independent of the court. The

King

hearing of his misbehaviour, complained that he had not one to revenge

him on a wretched priest for the many insults he had put upon

him. Hereupon four of his domestics, in hopes to gain favour, set

out immediately for Canterbury, and beat out Thomas's brains with

clubs, as he was saying vespers in his own cathedral, in so cruel a

manner, that the altar was covered with blood. King Henry subdued

Ireland, and died there in 1189, in the 34th year of his reign.

RICHARD I.

succeeded his father Henry II. and was no sooner crowned than he took

upon him the cross, and went with Philip, King of France, to the Holy

Land in 1192. On

his return he was detained by the Emperor

Henry VI. and was obliged to pay 100,000 marks for his ransom. In

a war which succeeded between England and France, Richard fought

personally in the field, and

gained a complete victory over the enemy, but was afterwards shot by an

arrow at the siege of the Castle of Chalus, and died of the wound April

6, 1199.

JOHN, the fourth son of Henry II. took possession of the crown on

Richard's decease, though his nephew Arthur of Bretagne, son of his

elder brother Geoffrey Plantagenet, had an undoubted title to it.

His encroachments on the privileges of his people called forth the

opposition of the spirited and potent Barons of that day: John

was reduced to great straits; and Pope Innocent III. with the usual

policy of the Holy Fathers, sided with John's disaffected subjects, and

fulminated the thunders of the church against him, till he had brought

him to his own terms: the King surrendered his crown at the feet of the

Pope's Legate, who returned it to him on his acknowledging that he held

it as the vassal of the Holy See, and binding himself and successors to

pay an annual tribute thereto. The Barons and their cause were to

be sacrificed to the Pope's interest, and the Legate commanded them to

lay down their arms; they were however bold enough to make head against

this powerful league, and by their steady opposition to the King, and

their moderate demands when their efforts were crowned with success,

immortalized their names: John was obliged to sign out two famous

charters -- the first called Magna Charta, or the Charter of Liberties;

the second the Charter of Forests; which two charters have since been

the foundation of the liberties of this nation. Some time after,

having thrown himself into a fever by eating peaches, he died at Newark

October 28, 1216.

HENRY III. succeeded his father John in 1216, being but nine years

old. He reigned 56 years, during the greatest part of which he

was

embroiled in a civil war. He founded the house of converts,

and an hospital, in Oxford, and died at St. Edmundsbury in 1272.

EDWARD I. though in the Holy Land when his father died, yet succeeded

him, and proved a warlike and successful Prince. He made France

fear him, and forced the King of Scotland to pay him homage. He

created his eldest son Prince of Wales, which title has been enjoyed by

the eldest son of all the Kings of England ever since. In his

last moments he exhorted his son to continue the war with Scotland, and

added, "Let my bones be carried before you, for I am sure the rebels

will never dare to stand the sight of them." He died of a bloody

flux at Burgh on the sands [sic],

a small town in Cumberland, July 7, 1337, having reigned 34 years, and

lived 68.

EDWARD II. succeeded his father, but proved an unfortunate Prince,

being hated by his nobles, and slighted by the commons: he was first

debauched by Gaveston his favourite, and afterwards by the two

Spencers, father and son, whose oppressions he countenanced to the

hazard of his crown. But the Barons taking up arms against the

King, Gaveston was beheaded, the two Spencers hanged, and he himself

forced to to resign the crown to Prince Edward his son. Soon

after which he was barbarously murdered at Berkeley Castle, by means of

Mortimer, the Queen's favourite. He reigned twenty

years, and was buried at Gloucester.

EDWARD III. who succeeded his father on his resignation, claimed the

crown of France, and backed his claim by embarking a powerful army for

that country, where he made rapid conquests: the Scots favouring the

French, invaded Cumberland, but were defeated by Edward's Queen

Philippa, who took David Bruce, their King, prisoner. Edward's

eldest son, sirnamed the Black Prince, gained two surprizing [sic]

victories, one at Cressi,

the

other at Poitiers, in which he took King John, with his youngest son

Philip, prisoners. Thus England had the glory to make two Kings

prisoners in one year. This reign is also memorable for the

institution of the most noble Order of the Garter, and for the title of

Duke of Cornwall being first conferred upon the Black Prince, and

continued as a birthright to the Prince Royal of England.

In this reign lived John Wickliff, who strenuously opposed the errors

of the Romish Church. Peter's Pence were now also denied to the

church of Rome; and the manufacture of cloth was first brought into

England.

Edward the Black Prince die in 1336, and his untimely end hastened that

of his father, who died soon after at Shene, in Surry,

having reigned thirty

years, and was buried at Westminster.

RICHARD II. son to Edward the Black Prince, succeeded his grandfather;

but he had neither his wisdom nor good fortune. He was born at

Bourdeaux in France: his

conduct in England made his reign very uneasy to his subjects, and at

last deprived him of his crown. He raised a tax of 5d. per head,

which caused an insurrection by the influence of Wat Tyler, who being

stabbed by William Walworth, Mayor of London, the storm was quelled.

The smothering of the

Duke

of Gloucester, and the unjust seizure of the Duke of Lancaster's

effects, with an intent to banish his son, were the two circumstances

which completed the King's ruin.

For after this tyranny and cruelty, being forced to resign the crown,

he was confined in Pomfret Castle, in Yorkshire, where being

barbarously murdered, he was buried at Langley, having reigned

twenty-two years. In his time lived Chaucer, the famous poet.

The

House of Lancaster, called the RED ROSE.

HENRY IV. who succeeded his cousin

Richard on his resignation in 1399, was the son of John of Gaunt, Duke

of Lancaster, who was fourth son of Edward III. In his turbulent

reign, which lasted thirteen years and a half, we find little

remarkable, except the act then passed for burning the Lollards or

Wickliffites,

who separated from the church of Rome.

HENRY V. succeeded his father, and, though a loose Prince in his youth,

proved a wise, virtuous and magnificent King. He banished all his lewd

companions from court, and claimed the English title to the crown of

France in so heroic and effectual a manner, that with 14,000 men he

beat the French at Agincourt, though 140,000 strong. Hereupon Queen

Katherine prevailed upon her husband Charles VI. then King of France,

to disinherit the Dauphin, and to give Katherine his daughter to Henry,

so that he was declared heir to the crown of France, and regent during

the King's life, which measures were ratified and confirmed by the

states of that kingdom, though he did not live to sit on the

throne. He reigned but ten years, died at Vincennes, a

royal palace near Paris, and was buried at Westminster, in 1422, in the

39th year of his age.

HENRY VI. when only eight years old, succeeded his father, but was no

less unfortunate at home than abroad; and though he was crowned at

Paris King of France, in the year 1423, yet he lost all that his

predecessors had acquired in that kingdom, Calais only excepted.

The crown of England was disputed between him and the house of York;

which occasioned such civil wars in England as made her bleed for 84

years, when all the Princes of York and Lancaster were either

killed in battle or beheaded. The

French laying hold of this favourable opportunity, shook off the

English yoke, and recovering their liberty in five years, placed the

young Dauphin upon the throne, who was then Charles VII. The

crown of England was now settled by Parliament upon the House of York

and their heirs, after the death of King Henry, whose heirs were

excluded for ever. This Prince passed through various changes of

life, and was at last stabbed to the heart by Richard Duke of

Gloucester, who had before murdered Edward, the only son of this

unfortunate King.

The

House of York, called the WHITE ROSE.

EDWARD IV. who had dispossessed Henry

VI. in 1460, was the first King of the line of York, and nobly

maintained his right to the crown by mere dint of arms; till at last

subduing the party which opposed him, he was crowned at Westminster

June 28, 1461. In this King's reign the ART OF PRINTING was first

brought into England. At this time also the King of Spain was

presented with some Cotswold sheep, from whose breed, 'tis said, came

the fine Spanish wool, to the prejudice of England. Edward

reigned 22 years, and was buried at Windsor in 1483.

EDWARD V. eldest son of Edward IV. succeeded his father when only

twelve years old; but his bloody uncle, Richard Duke of Gloucester,

caused both him and his brother to

be smothered in their beds in

the

Tower of London, in the second month of his reign, and before his

coronation.

RICHARD III. having dispatched his two nephews, succeeded to the crown,

and was the last King of the House of York. He was an usurper,

and his cruelty had incensed the Duke of Buckingham, his favourite, to

such a degree, that he contrived his ruin, and offered the crown to

Henry Earl of Richmond, the only surviving Prince of the House of

Lancaster, then at the court of France, on condition that he would

marry Elizabeth, the eldest daughter of Edward IV. in order to unite

the Houses of York and Lancaster -- Richard being informed of the

affair, ordered the Duke to be instantly beheaded without a

trial. However, this did not discourage Henry, who had accepted

the offer. He came over with a small force, and landed in Wales,

where he was born, his army increasing as he advanced. At length

having collected a body of 5000 men, he attacked King Richard in

Bosworth field, in Leicestershire, in 1485. Richard fought

bravely till he was killed in the engagement, which made way for Henry

to the crown of England.

THE

MODERN HISTORY OF ENGLAND.

CHAP. IV.

We shall divide this branch of English history into four periods,

namely: 1. The Kings of the House of Tudor. 2. The Kings of the

Stuart family. 3. King William of the House of Orange, and Queen

Anne. 4. The Kings of the House of Hanover.

The

House of TUDOR.

HENRY VII. succeeded Richard III. in

1485: he obtained the crown by force of arms, tho' he pretended a tight

to it by birth; being of the House of Lancaster. The name of his

father was Edmund Tudor, Earl of Richmond; and he married Elizabeth,

the daughter of King Edward IV. by which marriage the Houses of York

and Lancaster were united. This Prince had great sagacity, but

was very cruel and unjust. Edward Plantagenet, Earl of Warwick,

and the last Prince of the House of York, was beheaded by him for

attempting his escape, after being imprisoned from nine years old;

for which cruel

act Henry's name will be hated for ever. As he grew old, he

grew covetous, and to increase his treasure, he caused all penal laws

to be put in execution. His chief instruments herein were Empsom

and Dudley, who afterwards paid dear for their extortion. He

built the chapel at Westminster which is at this day called Henry the

Seventh's. The 48 gentlemen of the privy chamber, and the band of

gentlemen pensioners, were first settled in his reign. He died at

the palace of Richmond, which he built, and left in ready money to his

successor 1,800,000l. having reigned 24 years.

HENRY VIII. born at Greenwich, in 1491, the only surviving son of Henry

VII. came to the crown in the 18th year of his age, and in 1509.

He reigned for some years with great applause; but being vitiated by

Cardinal Woolsey, luxury and cruelty obscured his virtues, and stained

his former glory. He had six wives, of whom he divorced two, and

caused two to be publicly beheaded. In his reign began the

reformation; and the King was, by act of parliament, declared supreme

head of the church of England. Before he fell off from the Pope,

he wrote a book against Luther. On this account Pope Leo honoured

him with the title of defender of the faith; which the parliament made

hereditary to all succeeding Kings of England. His government was

more arbitrary and severe than that of any of his predecessors

since William the Conqueror. He reigned about 38 years, died Jan.

28, 1547, and was buried in Windsor chapel.

EDWARD VI. only son of Henry VIII. succeeded his father at ten years

old; and in the six years during which he reigned, he, by the

indefatigable zeal of Archbishop Cranmer, made a great progress in the

reformation. This good Prince founded our two famous hospitals,

called Christchurch and St. Thomas, one in the city of London, the

other in the suburbs. This reign is memorable for the discovery

of the north-east passage to Archangel, made by Richard Chalinour, till

then unknown, and since become the common passage from Asia into

Europe. Edward reigned but six years, and was buried at

Westminster.

MARY, eldest daughter of Henry VIII. by his first wife, succeeded her

half brother Edward VI. She restored the Roman Catholic Bishops,

and commenced a hot persecution against the protestants; in which

Archbishop Cranmer, and six other Bishops, were burnt alive. In

her reign, Calais was taken by the French, after it had been in our

possession 200 years; and the same year, which was 1558, she died of

grief for the loss of that city. With her life ended a reign,

begun,

continued, finished in blood, and happy in nothing but its short

duration. She was

buried at Westminster.

ELIZABETH, daughter

of Henry VIII. by Anna Bullen, his second wife, succeeded her

half-sister Mary. She proved an

excellent Queen, the glory of her sex, and admiration of the age she

lived in. She was crowned at Westminster, Jan. 15,

1558. In her time the protestant religion was again

restored. She humbled the pride of Spain, both in Europe and

America. Memorable is the year 1588, for the Spanish invasion

attempted by King Philip, with his invincible armada; the

greatest part of which was destroyed by the English fireships and a

providential storm. The very names of our chief commanders,

Howard, Norris, Essex, Drake, and Raleigh, struck a terror in her

enemies. They took and burnt several places in Spain,

particularly Cadiz and the Groyne;

intercepted their plate fleets, and

reduced that haughty monarch so low, that he has never since recovered

it. This Queen quelled the two rebellions of O'Neal

and

Tir-Owen

in Ireland. She protected the new republic of Holland,

and the protestants of France. She commanded the ocean, which

spread her fame around the globe, and made her name respected every

where. With much reluctance she signed the dead warrant [sic]

for the execution of Mary

Queen of Scots, charged with high treason. She grieved much for

the death of the Earl of Essex, whose fall was owing to her favour, and

survived him only two years. In her reign the two English

inquisitions were erected, I mean the Star-Chamber, and the High

Commission Court, which grew oppressive, and the judges so arbitrary,

that they were suppressed by an act of Charles I. She had a

peculiar taste for learning, which flourished in her reign. She

spoke five or six different languages, translated several books from

the Greek and French, and took great pleasure in the study of

mathematics, geography, and history. She died in 1603, in the

45th year of her reign, and the 70th year of her age, leaving her

kinsman James VI. of Scotland, her successor.

The

STUART FAMILY.

JAMES I. of England, arrived at London

May 7, 1603, and the feast of St. James following was fixed for his

coronation. In 1604, Nov. 5, the powder plot was

discovered, the memory whereof has been hitherto religiously observed.

Among the

remarkable things of this

reign, may be reckoned the two visits his Majesty received from

Christian IV. King of Denmark, whose sister Ann was King James's

consort: the creation of a new order called Baronets, next to a Baron,

and made hereditary: the fall of Lord Chancellor Bacon, and of Sir

Walter Raleigh, at the instigation of the Spanish Ambassador: the

office of the master of the ceremonies was first established. As

to the

character of this Prince, it must be confessed, that he was too much of

a scholar, and too little of the soldier. Though he was brought

up in the Scotch presbytery, he thought episcopacy so necessary for the

support of his crown, that he often used to say, No Bishop, No King. He died at

Theobalds, March 27, 1625, in the 23rd year of his reign, and 59th year

of his age. Thus ended a peaceable but inglorious, a plentiful

but luxurious reign, to make room for another more turbulent and

tragical.

CHARLES I. the only son of King James, succeeded next: he was born at

Dumferling, in Scotland, 1600, and crowned at Westminster, 1625.

His crown may be called a crown of thorns, as his reign ended in

blood. He married Henrietta, daughter to Henry IV. King of

France, who was bigotted to the catholic religion, and gained the

ascendancy over him. His wonderful compliance with the Queen

caused him to act in many respects contrary to the laws of the kingdom,

and his unbounded favour to the Duke of Buckingham, incensed the people

to that degree, that this favourite was afterwards stabbed by Felton,

merely for the public good. These, and such like weaknesses, made

him continually at variance with the parliament, which at last broke

out into a civil war. Several battles were fought between the

royalists and republicans or rumps.

The King

was taken prisoner by the Scots, who sold him to

the parliament for 200,000l.

Hereupon the parliament erected a high court of

justice, and gave them power to try the King; and though the

generality of the people were against such arbitrary proceedings, yet

they arraigned him of high-treason. The King maintained his

dignity, and refusing to acknowledge the authority of these pretended

judges, had sentence of death passed upon him, and was accordingly

beheaded on a scaffold erected for that purpose, before the palace,

Jan. 30, 1648. In this reign two great ministers, viz.

Archbishop Laud, and the Earl of Strafford, were beheaded.

CROMWELL, one of the most considerable members of the high court who

condemned King Charles, was now sent to subdue Ireland. After

which he marched against the Scots, who had taken up arms in favour of

the late King. The Dutch also, who had sent a fleet to assist the

King, having met with many losses and disappointments, sued for peace,

which Cromwell sold them at an exorbitant price. Now Cromwell was

made Lord Protector to the British dominions, and acted with the same

authority as if he had been King. He was a terror both to France

and Spain, and died Sept. 3, 1658. His son indeed succeeded to

that high station, which his father filled with universal applause; but

having neither an equal share of ambition, nor a head turned for

government, modestly resigned to the right heir

CHARLES II. son of Charles I. succeeded his father, but was

kept from

the crown above eleven years, during which time England was reduced to

a commonwealth. The King was at the Hague when his father was

beheaded. But on his yielding to some conditions imposed on him

by the kirk of Scotland, he was received by the Scots, and being

crowned at Scoon,

they sent an army with him into England to recover

that kingdom; which being totally defeated at Worcester, he wandered

about for six weeks, and made his escape to France, then to Spain, but

without any hopes of restoration, till the death of Oliver

Cromwell: when a free parliament, having met in April 1660, voted

the return of King Charles II. as lawful heir to the crown. The

power of the Rump Parliament, by the conduct and courage of General

Monk, had been on the decline for some time, and the King's interest

greatly increased, especially in the city of London, where he was

proclaimed May 8. He landed at Dover, and made a most magnificent

entry, May 29, 1660, being his birthday; and the 23d [sic]

of April following, being

St. George's day, he was crowned at Westminster with great state and

solemnity. Among the remarkable things of this reign, we may

reckon the parting with Dunkirk to France for a paltry sum; the blowing

up Tangier in the Streights, after immense sums had been expended to

repair and keep it; the

shutting up the Exchequer when

full of loans,

to the ruin of numerous families; the two Dutch wars, which ended

with no

advantage on either side, but served only to promote the French

interest; the great plague with which this nation was visited during

the first Dutch war; the fire of London that happened soon after; and

the Popish plot, for which many suffered death. On the 2d of Feb.

1684, the King fell sick of an apoplexy; he died four days after, in

the 37th year of his reign, and was privately buried at Westminster.

JAMES II. succeeded his brother Charles, but proved very unfortunate to

himself and his people, on account of his zeal for the Romish

religion. He invaded the rights of the universities, and made

Magdalen

College in Oxford a prey to his violence. He sent seven bishops

as criminals to the tower, who upon trial were honourably

acquitted. Father Peters, a Jesuit, and several Popish Lords, sat

in the Privy Council, and some Popish Judges on the bench.

The Pope sent a Nuncio from Rome, who was suffered to make his public

entry in defiance of our constitution. These barefaced practices

made the Protestant party think it high time to check the growth of

popery. Hereupon the Prince of Orange was requested to vindicate

his consort's right, and that of the three nations. In the

beginning of this reign the Duke of Monmouth was proclaimed King in the

West, in opposition to King James; but his party being defeated, he was

beheaded July 15, 1685. Judge Jeffries was afterwards sent

by the King to try those who had

assisted the Duke, of whom he hanged no less than 600, glorying in his

cruelty, and affirming, that he had hanged more than all the Judges

since William the Conqueror. The Chevalier St. George

was born July 10, 1688, two days after the bishops were

imprisoned.

The Prince of Orange landed at Torbay Nov. 5, and King James abdicated

the crown, and went over to France, Dec. 23. Hereupon an

interregnum ensued till the 13th of February, 1688-9, when William and

Mary, Prince and Princess of Orange, were offered the Crown, and

accepted it.

The

House of ORANGE.

WILLIAM III. and MARY II. succeeded James II. upon the vote of the

Convention. The day after their arrival in London, which was Feb.

13, 1688-9, they were seated under a canopy of state in the

Banqueting-house, and both Houses of Convocation waited upon them,

proffering them the crown in the names of the Lords Spiritual and

Temporal, and the Commons, assembled at Westminster: Accordingly they

were proclaimed King and Queen of Great-Britain the following day, and

solemnly crowned at the Abbey on the 21st of April. Several plots

were formed against the King, but all of them proved abortive. He

carried out a war with France, and with King James's party in

Ireland, for nine years successively,

till at last France was obliged to acknowledge him lawful King of

Great-Britain, in the peace of Ryswic, 1697. He died March 8,

1701, aged 51, after he had survived his consort Mary Stuart, daughter

to James II. five years, who died Dec. 21, 1696, and whose funeral was

performed with great elegance and solemnity. July 2, 1700,

William Duke of Gloucester, the only surviving issue of Princess Anne

of Denmark, departed this life at Windsor, aged twelve years. And

King James died at St. Germains in Sept. 1721.

ANNE, second daughter to James II. succeeded King William, whose

death was joy to France, but a great misfortune to England. Anne

was

born Feb. 6, 1664, and married George Prince of Denmark, who was High

Admiral of England, and a happy assistant to her in steering the ship

of state. She was crowned Queen of Great-Britain April 23,

1702. On the 4th of May following war was proclaimed at

London, Vienna, and the Hague, against France and Spain. The

success of this war is worthy admiration [sic],

and almost

incredible. The conquest of the Spanish Guelderland,

the Electorate of Cologn [sic],

and the Bishopric of Liege; the prodigious

victory over the French and Bavarians at Blenheim, under the surprising

conduct of the Duke of Marlborough; the retaking of Landau; the

conquering all the estates of the Duke of Bavaria in Germany; the

forcing the French and Bavarians out of their

lines in Brabant, which was deemed a thing impracticable; the battle of

Ramillies; the victory at Oudenard; the taking of Lisle and Tournay;

the defeat of the French army at Blarenies; the reducing of Mons,

&c. &c. are such events as will render her Majesty's reign

famous to all posterity. If we look towards Spain, how bold and

successful was our attempt upon Vigo, where we took and destroyed their

whole plate fleet, both men of war and others, to the amount of 38

sail, of which not one escaped: Did we not also take Gibraltar

with a small force in one morning, and keep possession of it against

the joint strength of France and Spain? Barcelona likewise being

taken by the English and Dutch, under the conduct of the Earl of

Peterborough, was soon after besieged by King Philip with a great army,

which was soon forced to a shameful retreat into France. Hereupon

Catalonia, Arragon, Valencia, and other provinces, submitted to Charles

III. by the influence of

her

Majesty's arms. Who could have expected the dismal turn of the

affairs of France and Italy, which happened in 1707, by the powerful

interest of England? A numerous army of French and Spaniards were

destroyed before the walls of Turin, by the Duke of Savoy and Prince

Eugene. Thus Piedmont was abandoned, the Mantuan, the Milanese,

the Modenese, Parmasan, and Montferrat, yielded up.

This Queen also brought about the strict union between England and

Scotland, after sundry fruitless attempts of the same kind for a

century past. In short, the successes of her reign justly

denominate her one of the most triumphant Monarchs of former ages, and

her piety and virtue will ever be acknowledged by the British nation.

The four last years of Queen Anne's reign were attended with much

perplexity, which was owing to her Ministers, who prevailed upon her to

consent to the peace of Utrecht; and, 'tis said, her death was

occasioned by her ill conduct, which she laid too much to heart.

She died Aug. 1, 1714;

and in her the

succession of the Stuart line ended.

The

House of HANOVER.

GEORGE I. who was heir-apparent to the crown of Great-Britain on the

death of Queen Anne, and which had been confirmed to him some years

before by various Acts of Parliament, and by a special article in the

peace of Utrecht, was born 1666, and proclaimed King the very day Queen

Anne expired. He landed at Greenwich Sept. 18, 1714, and was

crowned Oct. 20. A thorough change in the ministry was made on

his accession, wherein he distinguished his friends from his enemies.

Among the latter

the chief were the Duke of Ormond, the Earl

of Oxford, and the Viscount Bolingbroke, who were deemed to be firmly

attached to the interest of the Pretender. In 1715 a plot

was

supposed to be brooding in the West, where several gentlemen were

suspected of having a design to bring in the Pretender, and to place

him on the throne of his ancestors. He had already been

proclaimed King of Scotland, by the Earl of Mar, against whom the Duke

of Argyle marched. On the 13th of November they came to a

decisive battle near Dumblain, where the rebels were defeated, and put

to flight. At the same time a body of 5000 rebels assembled at

Preston in Lancashire, headed by the Earl of Derwentwater, of whom

General Wills, who commanded some of his Majesty's troops on the

borders of Scotland, being informed, he marched directly against them,

and obliged them to surrender prisoners of war. They were

afterwards sent up to London, and many of the ringleaders tried and

condemned. Among these were the Earls of Derwentwater and

Kenmure, who were beheaded on Tower-Hill; several others were executed

at Tyburn, and the remainder pardoned. Some other conspiracies

were formed against the King's person; but, by timely discovery,

prevented from being carried into execution. Aug. 2, 1718, the

quadruple alliance was signed between their Imperial, Christian, and

Britannic Majesties;

and the Spanish fleet was destroyed in the Mediterranean by the

English. In 1720 Spain acceded to the quadruple alliance, and a

fleet was sent into the Baltic in favour of Sweden. This year was

also remarkable for the South-Sea scheme,

by which many families were deluded and entirely ruined; and the

government was obliged to interpose, to prevent the ill consequences of

the people's despair. On enquiry into the affair it appeared,

that besides stock-jobbers and directors some persons of distinction

were concerned in it. This fatal stroke to the British trade was

in some measure remedied by the assiento contract, concluded at Madrid

in 1722.

In the same year, the funeral of the Duke of Marlborough, who, since

the accession of King George, had been restored to the honours he so

justly deserved, was solemnized with great pomp. In 1723, a

conspiracy for raising an insurrection was discovered; hereupon the

Duke of Norfolk, Lord North and Grey, the Bishop of Rochester, and

Counsellor Layer, were taken into custody; after a long trial the

Bishop was banished, and Layer was hanged. In 1724, the Ostend

East-India Company was established. In 1725 the Hanover treaty

was agreed to, between France, Great-Britain, and Prussia. June

11,

1727, George I. died at Osnaburgh, in the very chamber where he

was born, in the 67th year of his age, and the 13th year of his reign.

GEORGE II. was proclaimed as soon as as the news of his father's death

came to London, and his coronation was solemnized in October

following. The new Parliament met on the 2d of January, and chose

for their Speaker Arthur Onslow, Esq. and loyal and affectionate

addresses were presented

to the King by both houses. The land forces were fixed at 22,950

men, and the number of seamen at 15,000. An enquiry was

made

into the state of the public gaols, and from this it appeared that

great cruelties and oppressions had been exercised on the prisoners,

particularly on Sir William Rich, Baronet, who was found in the fleet

prison loaded with irons, by order of the Warden. For these and

the like barbarities, Thomas Bambridge, the Warden, and several of his

accomplices, were committed to Newgate. In May, 1729, his Majesty

declared his intentions of visiting his German dominions, and leaving

the Queen as Regent. His design in going to Germany was to

compromise some differences that had lately arisen between the Regency

of Hanover and the King of Prussia; and about this time the Duke of

Mecklenburgh was deposed by the Emperor, for his cruelty, tyranny, and

oppression. By the fall of Emperors and Kings it is that we learn

the Omnipotence of the Almighty, whose arm strengthens and supports the

crown of the righteous and takes away the kingdom from unjust

Princes. About this time great licentiousness prevailed among all

ranks of people, particularly among those of the lower class, who

indulged themselves in every kind of wickedness; and among other

methods of injuring their fellow subjects, circulated incendiary

letters, demanding sums of money of certain individuals, on pain

of reducing their houses to ashes;

this species of

villainy had never been known before in England. In the course of

the summer seven Indian Chiefs were brought over to England. In

1731 a duel was fought in the Green Park, between Sir William Pulteney

and Lord Hervey, on account of a remarkable political pamphlet.

Lord Hervey was wounded, and narrowly escaped with his life. The

Latin tongue was abolished in all law proceedings, which were ordered

for the future to be in English. Rich. Norton, Esq. of Southwick,

in Hampshire, left his estate of 600l.

per annum,

and a personal estate of 60,000l. to

be disposed of in charitable uses by the

Parliament. One Smith, a book-binder, and his wife, being reduced

to extreme poverty, hanged themselves at the same time, and by common

consent, after having made away with their only child.

On the 27th of April, 1736, his Royal Highness Frederic, Prince of

Wales, espoused Augusta, sister to the Duke of Saxe Gotha.

In

the course of this year a remarkable riot happened at Edinburgh,

occasioned by the execution of one Wilson, a smuggler. Porteus,

captain of the city guard, a man of a brutal disposition, and abandoned

morals, being provoked by the insults of the mob, commanded his

soldiers to fire upon the crowd, by which precipitate orders several

innocent persons were killed; Porteus was tried and condemned to

die, but obtained a reprieve from the Queen, who was then

Regent. The mob, however, were [sic]

determined to execute the

sentence; they accordingly rose in a tumultuous manner, forced open the

prison doors, dragged forth Porteus, and hanged him on a dyer's pole;

after which they quietly dispersed. On the 24th of May,

1738, the Princess of Wales was delivered of a Prince, who was

christened by the name of George, now our most gracious

Sovereign. One Buchanan, a sailor, who had been condemned for

murder, was cut down from the gallows by his companions, who actually

brought him to life, and carried him off in triumph.

War was declared in form against Spain, at London and Westminster, Oct.

23, 1739. The same year Admiral Vernon destroyed Porto Bello, and the

March following demolished Fort Chagre. In 1740 there was a

severe and lasting frost, which extended all over Europe, and

occasioned a fair to be kept on the River Thames. In 1741 Admiral

Vernon, with a strong fleet, joined with General Wentworth, who had a

considerable number of forces under his command, made an unsuccessful

attempt on Carthagena [sic];

the greater part of the land forces being either killed or cut off by

an epidemical distemper. In 1742, Captain Middleton made a

fruitless attempt to discover the North West passage into the South

Seas. The year following the battle of Dettingen was

fought. There was also this year a bloody engagement before

Toulon, between the English fleet and that of the French and

Spaniards; when that brave commander

Captain Cornwall was killed in the Marlborough, after a most resolute

and surprising resistance. Commodore Anson returned to England,

having made a voyage round the globe; and war was mutually declared

between England and France.

In 1745 the battle of Fontenoy was fought, in which the French had the

advantage, which was followed by the taking of Tournay. A

rebellion broke out in Scotland; the rebels defeated Sir John Cope, at

Preston Pans, came forward into England, took Carlisle, and marched to

Derby, from whence they were obliged to make a precipitate retreat,

being closely pursued by the Duke of Cumberland, who retook

Carlisle. When the rebels were returned into Scotland, they

defeated the King's forces under General Hawley, near Falkirk, and laid

siege to Stirling, but raised it on the Duke's approach. This

year Cape-Breton was taken by Admiral Warren. In 1746 the

memorable battle of Culloden, in Scotland, was fought, wherein the

rebels were totally destroyed: The Earls of Balmerino and Kilmarnock,

with Mr. Ratcliff, brother to the late Earl of Derwentwater, were taken

prisoners, and beheaded on Tower-Hill; as was Lord Lovat in the year

following. Now also the French took all Dutch Flanders, and there

was a battle between them and part of the allied army, after which the

latter retreated under the cannon of Maestricht. Admirals Anson

and Warren, after a hot engagement, took several French men of

war in the Mediterranean, among which was the ship in which their

Admiral sailed. In 1748 a Congress was held at Aix-la-Chapelle

for a general pacification, and the articles of peace therein agreed to

were signed in April.

A Bill was passed for the encouragement of the British herring fishery;

and a proclamation issued for inciting disbanded soldiers and sailors

to settle in Nova Scotia. Mr. Pelham now lowered the interest of

money in the funds, first to three and a half per cent.

afterwards to three.

The importation of iron from America was allowed; and the African trade

laid open.

In the year 1752, the French spirited up the Indians against our

colonies of Nova Scotia, and built a chain of forts on the back of our

American settlements. This occasioned a new war, carried on with

great cruelty in those parts. Monckton drove the French from

their encroachments in Nova Scotia; and General Johnson gave them a

defeat; but Braddock, through his own rashness, was defeated and

slain. The English took many ships from the enemy, without

declaring war.

In 1756, the Hessians and Hanoverians were brought over, to the number

of ten thousand. Presently after Minorca was taken by the French;

and Admiral Byng was shot at Portsmouth for not having relieved

it. On the 17th of May, war was declared in form,

and the King entered into

a treaty with the Empress of Russia

for the

security of Hanover; and afterwards into an alliance with

Prussia. This was followed by an unnatural [sic]

treaty

between France and the

Queen of Hungary, to which the Empress of Russia acceded. And a

war was

kindled by the

intrigues of France

between Prussia and

Sweden; while the Elector of Saxony favoured the Austrians. The

King of Prussia therefore entered Saxony, and obliged the Saxon troops

at Pirna to surrender prisoners of war. He invaded Bohemia,

defeated the Austrian General, and gained another victory near

Prague. But attacking the Austrians at a disadvantage near Kolin,

he was defeated, and obliged

to raise

the siege of Prague.

The French now passed the Weser, and drove the Hanoverians before

them. They made a stand however at Hastenbeck, under the Duke of

Cumberland, where they were

attacked,

and forced to retreat towards Stade, and laid down their arms in

consequence of the treaty of Closterseven.

In the East-Indies we were also successful; for, by Colonel Clive's

vigilance and courage, the province of Arcot was cleared of the enemy,

the French

general taken prisoner, and the favourite Nabob, whom we supported, was

reinstated in his government. But some months after, the Viceroy

of Bengal declared against the English, and took Calcutta by

assault. Here one hundred and forty-six persons were crowded into

a narrow prison, called the Black-Hole, where they were suffocated

for want of air, only

twenty-three surviving; several of whom died by putrid fevers, after

they were set free.

The Dutch at Batavia now dispatched seven armed ships to Bengal, having

eleven hundred land forces, with orders strongly to fortify their

settlement at Chincura, and secure the salt-petre trade to

themselves. But the ships were all taken by three English

East-India ships, which were in the river, and their troops were

totally defeated at land by Colonel Ford.

Colonel Coote also took the city of Wandewash,

reduced the

fortress of Carangoly, and defeated Lally.

This was followed by the surrender of the city of Arcot.

Pondicherry now sustained a siege in turn, and the French therein were

reduced to feed on dogs and cats. Eight crowns were given for the

flesh of a dog. At length the English took possession of the

place. And this conquest terminated the power of France in India.

Mr. Pitt was at the head of the English Ministry, when Louisbourg in

Cape Breton was besieged by General Amherst, and surrendered by

capitulation. The French lost a fine navy in the harbour.

Fort Du Quesne

also was taken. But the operations against Crown Point and

Ticonderoga miscarried.

The year 1759 was remarkable for the conquest of Canada. The

French deserted Crown Point and Ticonderoga, which were possessed by

General Amherst. Sir William Johnson defeated them, and

became master of the Fort of Niagara. And the

Admirals Saunders, Holmes, and Durel, sailed for Quebec, attended by a

land army, under General Wolfe. In the battle which ensued, both

Wolfe and Montcalm, the chief commanders on each side, were slain, and

Quebec surrendered.

In 1760 the French forces endeavoured to recover Quebec, but the place

was relieved by an English fleet under Lord Colvill. Montreal

submitted to General Amherst, and that extensive country fell totally

under the power of Great Britain; a larger territory than ever was

subject to the Roman empire. The prodigious march of Amherst, on

this occasion, can be compared only to that of Jenghiz Can,

or Tamerlane, who over-ran all Asia with their Tartars.

In Europe the operations of war were astonishing, and the great efforts

of the King of Prussia secured his safety beyond all human

expectation. Almost the whole power of the Continent was united

against him. The King of Great Britain, his only ally, seemed

inclined to forsake him. In this terrible situation he relied on

his natural subjects, and still adhered to his fortitude. Yet he

expostulated warmly, and his expostulations at last succeeded.

The French forces, and those of the Imperialists, had made a successful

campaign in the summer; yet seemed determined that the rigour of the

winter should not interrupt their proceedings. In the depth of

it, they laid siege to Leipsic,

and

were confident of carrying that important city. This greatly

alarmed his Prussian Majesty. He contrived his measures so

artfully, as to appear before the place when he was least

expected. Vanquished as he was, the terror of his arms raised the

siege. The French army, though greatly superior in number, rose

and retreated with precipitation.

His Prussian Majesty, not satisfied with having raised the siege of

Leipsic, followed the French army, whose fears, he imagined, would

befriend him. He came up with them near a little village, called

Rosbach. An action

came

on, and he obtained one of the most signal victories recorded in

history. Had not the night saved them, their whole army had been

devoted to destruction.

In another part of the empire the Austrians were again victorious, and

took the Prince of Bevern, the King of Prussia's Generalissimo,

prisoner. The King himself, in the depth of winter, made a march

of two hundred miles, and engaged the enemy in the neighbourhood of

Breslau, the capital of Silesia. He was much inferior in

strength, but his forces were disposed with such admirable

judgment [sic],

that he

gained a compleat [sic]

victory, in which he took

fifteen thousand prisoners. Breslau itself, after the battle,

surrendered to the Conqueror, tho' it had a garrison of ten thousand

men. These successes disheartened his enemies, and raised the

spirit of his friends.

The magnanimous King of Prussia now began to fight with his enemies

upon more equal terms. He attacked them every where, was attended

for the most part with remarkable success, and rarely met with any

considerable disadvantage. He carried on the campaign throughout

the winter, escaped many dangers, was exhausted by no fatigues, nor

terrified by any numbers.

England is so happily situated, that she has little need to concern

herself with the disturbances on the Continent. Yet the people in

general at this time seemed in a disposition to encourage and assist

the German subjects of their King.

At the meeting of the Parliament, the reasonableness of engaging in a

war upon the Continent was taken into consideration, and

admitted. Liberal supplies were granted, to enable the army, now

collected in the King's Hanoverian dominions, to act with vigour, in

conjunction with the King of Prussia. Supplies were also granted

to his Prussian Majesty.

A spirit of enterprise now seemed to animate all ranks of people.

A body of British forces was sent into Germany, under the command of

the Duke of Marlborough, to assist Prince Ferdinand of Brunswick and

the Hanoverians; and who afterwards behaved with great bravery.

The English fleet in the mean time invaded France, and burnt the French

shipping at St. Malo's. It then moved towards Cherburgh,

but was obliged by the weather

to return home.

On the 1st of August, 1758, the fleet under Commodore Howe, with the

transports, again set sail for Cherburgh. They landed with little

opposition from the French, and entered the town. Immense sums

had been there laid out upon the fortifications, and the harbour was

one of the strongest in Europe. The work of all this labour and

expence [sic]

was now

totally destroyed by the English, who found more difficulty in

demolishing than in conquering the place. All the ships in the

harbour were burnt, and a contribution raised upon the town.

On the 16th of August, the British fleet and army having remained in

France unmolested for ten days, set sail for Cherburgh, and carried off

all the brass cannon and mortars taken there.

The English troops landed again in the Bay of St. Lunar, in the

neighbourhood of St. Malo, but found it impracticable to make any

impression upon the place. While the troops were ashore the

Commodore found himself obliged, from the danger of the coast, to move

up to the Bay of St. Cas, about three leagues to the westward; while

the army marched over land to the same place, where they all embarked,

except the last division, consisting of the grenadiers of the army, and

the first regiment of guards. These were attacked by the Duke

d'Aiguillon, Governor of Brittany, at the head of twelve

battalions, and six squadrons of regulars,

besides two regiments of militia, against whom, though they made a most

gallant resistance, about six hundred of them were killed, and four

hundred taken prisoners, not being able to reach the boats.

The English had already made themselves masters of Senegal and Goree,

in Africa; and

though they had

now lost Minorca, yet they remained victorious in the Mediterranean,

and continued to ruin the French marine.

Towards the end of the year, a squadron of nine ships of the line, with

sixty transports, containing six regiments of foot, was fitting out for

the conquest of Martinico.

But tho' a conquest of that island was

judged, after a slight attempt, to be impracticable, they achieved the

more important reduction of Guadaloupe.

On the 28th of July, the Hereditary Prince was detached with six

thousand men to cut off the enemy's communication with Paderborn.

And on the 29th, Prince Ferdinand advanced from his camp on the Weser,

leaving a body of troops under Wangenheim, on the borders of that river.

The next day was fought the battle of Minden, as glorious to the

English, as those of Cressy

and Agincourt had been to their ancestors. The centre of the

French was entirely composed of horse, who attacked six English

regiments, supported by two battalions of Hanoverian guards.

These sustained the whole shock of the battle, and, to the

amazement of the German General

himself, obtained a compleat victory. The French lost seven

thousand men, and the English twelve hundred.

The French were greatly disappointed in their views by sea this

year. Thurot, a marine freebooter,

with three ships and a

considerable body of

land forces, landed in Ireland, and alarmed the people of Carrickfergus

. Putting to sea again, he was met by three British

frigates, of a force inferior to his own, and after a severe encounter

he was killed, and his ships led in triumph by the English commanders

to the Isle of Man.

A grand fleet was intended to invade England, under Marshal Conflans

and the Duke d'Aiguillon; but this fleet was ruined by Admiral Hawke on

the 20th of November.