Weights & Measures |

A BRIEF ACCOUNT OF THE

SEVEN WONDERS OF THE WORLD.

THO' the Pagans were grossly ignorant of

the most important truths, with respect to God and religion; yet the

virtuosi of this and preceding ages have been forced to acknowledge,

that their tastes were elegant, sublime, and well-formed, with respect

to works of sculpture, statuary, and architecture. As a proof of

this, in behalf of the ancients, 'tis only requisite we should take a

cursory view of those noble and magnificent productions of art,

commonly called THE SEVEN WONDERS OF THE WORLD.

(148)

The TEMPLE of EPHESUS.

THE first of these Seven Wonders was the Temple of Ephesus, founded by Ctesiphon, consecrated to Diana, and, (according to the conjectures of natural philosophers) situated in a marshy soil, for no other reason than that it might not be exposed to the violent shocks of earthquakes and volcanos. This noble structure, which was 425 feet long, and 220 feet broad, had not its bulk alone to raise it above the most stately monuments of art, since

it was adorned with 127 lofty and well proportioned pillars of Parian marble, each of which had an opulent monarch for its erector and finisher; and so high did the spirit of emulation run in this point, that each succeeding potentate endeavoured to outstrip his predecessor in the richness, grandeur, and magnificence of his respective pillar. As it is impossible for a modern to form a just and adequate idea of such a stupendous piece of art, 'tis sufficient to inform him, that the rearing of the Temple of Ephesus employed several thousands of the finest workmen of the times for 200 years: but as no building is proof against the shocks of time, and the injuries of the weather, so the Temple of Ephesus falling into decay, was, by the command of Alexander the Great, rebuilt by Dinocrates, his own engineer, the finest architect then alive.

The TEMPLE of EPHESUS.

THE first of these Seven Wonders was the Temple of Ephesus, founded by Ctesiphon, consecrated to Diana, and, (according to the conjectures of natural philosophers) situated in a marshy soil, for no other reason than that it might not be exposed to the violent shocks of earthquakes and volcanos. This noble structure, which was 425 feet long, and 220 feet broad, had not its bulk alone to raise it above the most stately monuments of art, since

(149)

it was adorned with 127 lofty and well proportioned pillars of Parian marble, each of which had an opulent monarch for its erector and finisher; and so high did the spirit of emulation run in this point, that each succeeding potentate endeavoured to outstrip his predecessor in the richness, grandeur, and magnificence of his respective pillar. As it is impossible for a modern to form a just and adequate idea of such a stupendous piece of art, 'tis sufficient to inform him, that the rearing of the Temple of Ephesus employed several thousands of the finest workmen of the times for 200 years: but as no building is proof against the shocks of time, and the injuries of the weather, so the Temple of Ephesus falling into decay, was, by the command of Alexander the Great, rebuilt by Dinocrates, his own engineer, the finest architect then alive.

(150)

The WALLS of BABYLON.

The WALLS of BABYLON.

THE works of the cruel, though ingenious

and enterprising Semiramis, next command our wonder and

admiration. These consisted of the walls erected about Babylon,

and the pleasant gardens formed for her own delight. This

immense, or rather inconceivable profusion of art and expence [sic], employed 30,000 men for

many years successively, so that we need not wonder when we are told by

historians, that these walls were 300 or 350 stadia in circumference

(which amount to 22

English miles), fifty cubits high [25 yards, or about 23 metres], and so broad that they could afford room for two or three coaches a-breast without any danger. Though ancient records give us no particular accounts of the gardens, yet we may reasonably presume, that if so much time and treasure were laid out upon the walls, the gardens must not have remained without their peculiar beauties: thus 'tis more than probable that the gardens of Semiramis charmed the wondering eye with unbounded prospect, consisting of regular vistas, agreeable avenues, fine parterres, cool grottos and alcoves, formed for the delicious purposes of love, philosophy, retirement, or the gratification of any other passion, to which great and good minds are subject.

(151)

English miles), fifty cubits high [25 yards, or about 23 metres], and so broad that they could afford room for two or three coaches a-breast without any danger. Though ancient records give us no particular accounts of the gardens, yet we may reasonably presume, that if so much time and treasure were laid out upon the walls, the gardens must not have remained without their peculiar beauties: thus 'tis more than probable that the gardens of Semiramis charmed the wondering eye with unbounded prospect, consisting of regular vistas, agreeable avenues, fine parterres, cool grottos and alcoves, formed for the delicious purposes of love, philosophy, retirement, or the gratification of any other passion, to which great and good minds are subject.

(152)

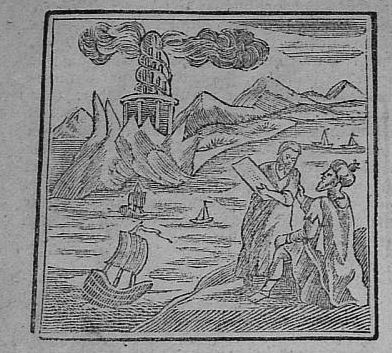

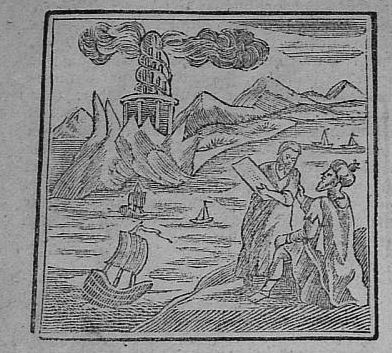

The TOMB of PHAROS.

The TOMB of PHAROS.

WE shall next take a view of the

splendid and sumptuous Tomb of Pharos,

commonly called the Egyptian Labyrinth. This structure, though

designed for the interment of the dead, had nevertheless the pomp of a

palace designed for a monarch, who thought he was to live for ever;

since it contained sixteen magnificent apartments, corresponding to the

sixteen provinces of Egypt; and it so struck the fancy of the

celebrated Dedalus [usually

called Daedalus], that from it he took the model of that re-

(153)

nowned labyrinth which he built in

Crete, and which has eternized [sic]

his

name, for one of the finest artists in the world.

[There seems to be some confusion here - this wonder is usually given as the Lighthouse of Pharos, and the woodcut clearly shows some kind of lighthouse. Conversely, the so-called Egyptian Labyrinth, while described by Herodotus in the 5th century BC as being more impressive than the pyramids, is not usually listed among the Seven Wonders. Flinders Petrie suggested it was located at Hawara near Fayyum, but it is hard to see how such a vast structure could disappear so completely - so it may actually still be waiting to be rediscovered. See www.catchpenny.org/labyrin.html]

[There seems to be some confusion here - this wonder is usually given as the Lighthouse of Pharos, and the woodcut clearly shows some kind of lighthouse. Conversely, the so-called Egyptian Labyrinth, while described by Herodotus in the 5th century BC as being more impressive than the pyramids, is not usually listed among the Seven Wonders. Flinders Petrie suggested it was located at Hawara near Fayyum, but it is hard to see how such a vast structure could disappear so completely - so it may actually still be waiting to be rediscovered. See www.catchpenny.org/labyrin.html]

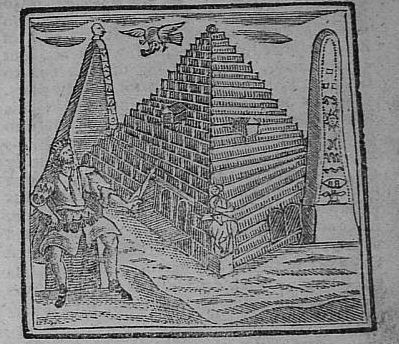

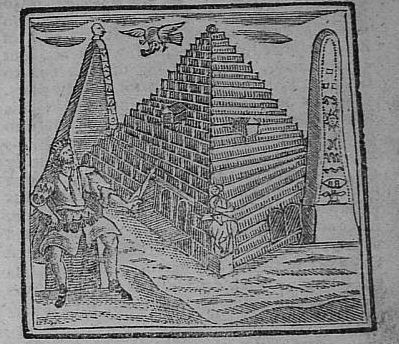

Of

the PYRAMIDS of

EGYPT.

IF the amazing bulk, the regular form,

and the almost inconceivable

duration of public or monumental buildings call for surprize [sic] and

astonishment, we have certainly just reason to give the Pyramids of

Egypt a place among the Seven Wonders. These buildings remain

almost as strong and beautiful as ever, 'till this very time. There are three of them; the largest of which was erected by Chemnis, one of the Kings of Egypt, as a monument of his power when alive, and for a receptacle of his body when dead [another name for Cheops, or Khufu]. It was situated about 16 English miles from Memphis, now known by the name of Grand Cairo, and was about 1440 feet in height, and about 143 feet long, on each side of the square basis. It was built of hard Arabian stones, each of which is about 30 feet long. The building of it is said to have employed 600,000 men for twenty years. Chemnis however was not interred in this lofty monument, but was barbarously torn to pieces in a mutiny of his people. Cephas [Chephren, Khafre(?)], his brother, succeeding him, discovered an equally culpable vanity, and erected another, though a less magnificent pyramid. The third was built by King Mycernius [Menaure, Menkare] according to some, but, according to others, by the celebrated courtesan Rhodope. This structure is rendered still more surprising, by having placed upon its top a head of black marble, 102 feet round the temples, and about 60 feet from the chin to the crown of the head [reference to the Sphynx?].

(154)

almost as strong and beautiful as ever, 'till this very time. There are three of them; the largest of which was erected by Chemnis, one of the Kings of Egypt, as a monument of his power when alive, and for a receptacle of his body when dead [another name for Cheops, or Khufu]. It was situated about 16 English miles from Memphis, now known by the name of Grand Cairo, and was about 1440 feet in height, and about 143 feet long, on each side of the square basis. It was built of hard Arabian stones, each of which is about 30 feet long. The building of it is said to have employed 600,000 men for twenty years. Chemnis however was not interred in this lofty monument, but was barbarously torn to pieces in a mutiny of his people. Cephas [Chephren, Khafre(?)], his brother, succeeding him, discovered an equally culpable vanity, and erected another, though a less magnificent pyramid. The third was built by King Mycernius [Menaure, Menkare] according to some, but, according to others, by the celebrated courtesan Rhodope. This structure is rendered still more surprising, by having placed upon its top a head of black marble, 102 feet round the temples, and about 60 feet from the chin to the crown of the head [reference to the Sphynx?].

(155)

The TOMB of MAUSOLUS.

The TOMB of MAUSOLUS.

THE next is the celebrated monument of

conjugal love, known by the name of the Mausoleum, and erected by

Artemesia, Queen of Caria, in honour of her husband Mausolus, whom she

loved so tenderly, that, after his death, she ordered his body to be

burnt, and put his ashes in a cup of wine, and drank it, that she might

lodge the remains of her husband as near to her heart as she possibly

could. This structure she enriched with such a pro-

fusion of art and expence, that it was justly looked upon as one of the greatest wonders of the world, and ever since magnificent funeral monuments are called Mausoleums.

It stood in Halicarnassus, capital of the kingdom of Caria, between the King's Palace and the Temple of Venus. Its breadth from N. to S. was 63 feet, and in circumference 411, and about 120 feet high. Pyrrhus raised a pyramid on the top of it, and placed thereon a marble chariot drawn by four horses. The whole was admired by all that saw it, except the philosopher Anaxagoras, who, at the sight of it, cried, "There is a great deal of money changed into stone."

(156)

fusion of art and expence, that it was justly looked upon as one of the greatest wonders of the world, and ever since magnificent funeral monuments are called Mausoleums.

It stood in Halicarnassus, capital of the kingdom of Caria, between the King's Palace and the Temple of Venus. Its breadth from N. to S. was 63 feet, and in circumference 411, and about 120 feet high. Pyrrhus raised a pyramid on the top of it, and placed thereon a marble chariot drawn by four horses. The whole was admired by all that saw it, except the philosopher Anaxagoras, who, at the sight of it, cried, "There is a great deal of money changed into stone."

(157)

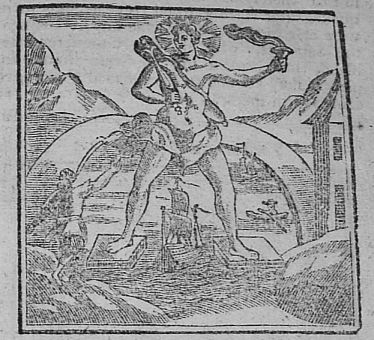

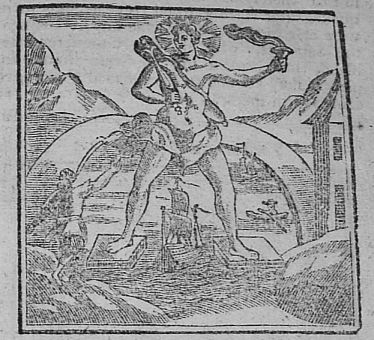

The COLOSSUS of the SUN.

The COLOSSUS of the SUN.

THE Colossus of Rhodes, is justly

accounted the sixth Wonder; a statue of so prodigious a bulk, that it

could not have been believed, had it not been recorded by the best

historians. It was made of brass by one Chares of Asia

Minor, who consumed twelve years in finishing it. It was

erected over the entry of the harbour of the city, with the right foot

on one side, and the left on the other. The largest ships could

pass between the legs without lowering their masts. It is said to

have cost 44,000l. [presumably

44,000 pounds Sterling] English money. It was 800

feet

in height, and all its members proportionable; so that when it was thrown down by an earthquake, after having stood 50 years, few men were able to embrace its little finger. When the Saracens, who in 684 conquered the island, had broken this immense statue to pieces, they are said to have loaded above 900 camels with the brass of it.

(158)

in height, and all its members proportionable; so that when it was thrown down by an earthquake, after having stood 50 years, few men were able to embrace its little finger. When the Saracens, who in 684 conquered the island, had broken this immense statue to pieces, they are said to have loaded above 900 camels with the brass of it.

The

IMAGE of Jupiter.

THE last, most elegant, and curious of

all these works, known by the name of the Seven Wonders, was the

incomparable statue

of Jupiter Olympus, erected by the Elians, a people of Greece, and placed in a magnificent temple consecrated to Jupiter. This statue represented Jupiter sitting in a chair, with his upper part naked, but covered down from the girdle, in his right hand holding an eagle, and in his left a sceptre. This statue was made by the celebrated Phidias, and was 150 cubits high [225 feet]. The body is said to have been of brass, and the head of pure gold. Caligula endeavoured to get it transported to Rome, but the persons employed in that attempt were frightened from their purpose by some unlucky accident.

(159)

of Jupiter Olympus, erected by the Elians, a people of Greece, and placed in a magnificent temple consecrated to Jupiter. This statue represented Jupiter sitting in a chair, with his upper part naked, but covered down from the girdle, in his right hand holding an eagle, and in his left a sceptre. This statue was made by the celebrated Phidias, and was 150 cubits high [225 feet]. The body is said to have been of brass, and the head of pure gold. Caligula endeavoured to get it transported to Rome, but the persons employed in that attempt were frightened from their purpose by some unlucky accident.