Seven Wonders |

Volcanos

(and some Roman numerals) |

Thus having given an Account of the Seven Wonders of the World, let us take a View of the Burning Mountains, or Volcanos, called Mount Vesuvius and Mount Ætna; than which there is, perhaps, nothing in the whole Course of Nature more worthy our Notice [sic] , or so capable of raising our Admiration; and which, when considered in a religious sense, may, with Justice, be said to be one of the wonderful Works of GOD.

MOUNT VESUVIUS stands about six miles from the city of Naples, and on the side of the Bay towards the East. The plains round it form a beautiful prospect, and on one side are seen fruitful trees of different kinds, and vineyards that produce the most excellent wine; but when one ascends higher, on the side which looks to the South, the face of things is entirely changed, and one sees a tract of ground, which presents only images of horror, viz. a desolate country covered with ashes, pumice-stones, and cinders; together with rocks burned up with the fire, and split into dreadful precipices. It is reckoned four miles high, and the top of it is a wide naked plain, smoking with sulphur in many places; in the midst of which plain stands

(161)

another high hill, in the shape of a sugar-loaf, on the top of which is a vast mouth or cavity, that goes shelving down on all sides about a hundred yards deep, and about four hundred over; from whence proceeds a continual smoke, and sometimes those astonishing and dreadful eruptions of flame, ashes, and burning matter, that fill the inhabitants around with consternation, and bear down and destroy all before it. Among the many eruptions which it has had, at different times, we need instance only one, which happened on the fifth of June, 1717, and is thus related by Mr. Edward Berkley, who was present at the time, in his letter to Dr. Arbuthnot in England, viz. That he with much difficulty, reached the top of Vesuvius on the 17th of April, 1717, where says he, I saw a vast aperture full of smoke, and heard within that horrid gulph certain odd sounds, as it were murmuring, sighing, throbbing, churning, dashing of waves; and, between while, a noise like that of thunder or cannon, attended constantly, from the belly of the mountain, with a clattering like that of tiles falling from the tops of houses into a street. After an hour's stay, the smoke being moved by the wind, I could discern two furnaces, almost contiguous; one on the left, which seemed to be about three yards diameter, glowed with red flames, and threw up red hot stones with a hideous noise, which, as they fell back, caused the fore-mentioned clattering.

On May 8, ascending to the top of Vesuvius, I had a full prospect of the crater, which ap-

(162)

peared to be about a mile in circumference, and a hundred yards deep, with a conical mount in the middle of the bottom, made of stones thrown up and fallen back again into the crater: And the left-hand furnace, mentioned before, threw up every three or four minutes, with a dreadful bellowing, a vast number of red hot stones, sometimes more than a 1000, but never less than 300 feet higher than my head, as I stood upon the brink, which fell back perpendicularly into the crater, there being no wind. This furnace or mouth was in the vortex of the hill, which it had formed round it. The other mouth was lower, in the side of the same new-formed hill, and filled with such red hot liquid matter as we see in a glass-house furnace, which raged and wrought as the waves in the sea, causing a short abrupt noise, like what may be imagined from a sea of quicksilver dashing among uneven rocks. This stuff would sometimes spew over, and run down the convex side of the conical hill, and appearing at first red hot, it changed colour, and hardened as it cooled, shewing the first rudiments of an eruption, or an eruption in miniature: All which I could exactly survey by the favour of the wind, for the space of an hour and a half; during which it was very observable, that all the vollies [sic] of smoke, flame, and burning stone, came only out of the hole to our left, while the liquid stuff in the other mouth worked and overflowed.

On June 5, after a horrid noise, the mountain was seen, at Naples, to spew a little out of

(163)

the crater, and so continued till about two hours before night on the 7th, when it made hideous bellowing, which continued all that night, and the next day till noon, causing all the windows, and, as some affirm, the very houses in Naples (about six miles distant) to shake. From that time it spewed vast quantities of melted stuff to the South, which streamed down the side of the mountain, like a pot boiling over.

On the 9th, at night, a column of fire shot at intervals out of its summit.

On the 10th, the mountain grew very outrageous again, roaring and groaning most dreadfully, sounding like a noise made up of a raging tempest, the murmur of a troubled sea, and the roaring of thunder and artillery, confused altogether. This moved my curiosity to approach the mountain. Three or four of us were carried in a boat, and landed at Torre del Greco, a town situate at the foot of Vesuvius to the S.W. whence we rode between four and five miles before we came to the burning river, which was about midnight; and as we approached, the roaring of the volcano grew exceeding loud and terrible. I observed a mixture of colours in the cloud over the crater, green, yellow, red, and blue. There was likewise a ruddy dismal light in the air, over the tract of land where the burning river flowed; ashes continually showering on us all the way from the sea-coast, which horrid scene grew still more extraordinary, as we came nearer the stream. Imagine a vast torrent of liquid fire rolling from the top down the side

(164)

of the mountain, and with irresistible fury bearing down and consuming vines, olives, fig-trees, houses, and, in a word, every thing that stood in its way.

|

Death, in a thousand forms,

destructive frown'd, |

|

And

Woe, Despair, and Horror rag'd around. |

Æneid II. by Pitt [i.e. Virgil's Aeneid, tr. Rev.

Christopher Pitt, 1753].

The largest stream of fire seemed half a

mile broad at least, and five miles long. During our return, at

about three o'clock in the morning, we constantly heard the murmur and

groaning of the mountain, which sometimes burst out into louder peals,

throwing up huge spouts of fire, and burning stones, which, falling

down again, resembled stars in our rockets. Sometimes I observed

two, and at others three distinct columns of flames, and sometimes one

vast one, that seemed to fill the whole crater; which burning columns,

and the fiery stones, seemed to be shot 1000 feet perpendicular above

the summit of the volcano.

On the 11th, at night, I observed it from a terrace, at Naples, to throw up incessantly a vast body of fire, and great stones, to a surprising height.

On the 12th, in the morning, it darkened the sun with smoke and ashes, causing a sort of an eclipse. Horrid bellowings, on this and the foregoing day, were heard at Naples, whither part of the ashes also reached.

On the 13th we saw a pillar of black smoke shoot upright to a prodigious height.

On the 15th, in the morning, the court and walls of our house in Naples were covered with ashes. In the evening a flame appeared in the mountain through the clouds.

On the 17th, the smoke appeared much diminished, fat, and greasy. And

On the 18th, the whole appearance ended, the mountain remaining perfectly quiet.

To this memorable account it cannot be amiss to add, that the first notice we have of this volcano's casting out flames, was in the reign of the Emperor Titus. At which first eruption, we are informed, that it flowed with that vehemence, that it entirely overwhelmed and destroyed the two great cities Herculaneum and Pompeia [now usually called Pompeii], and very much damaged Naples itself, with its stones and ashes.

In 471, if we may credit tradition, this mountain broke out again so furiously, that its cinders and liquid fire were carried as far as Constantinople; which prodigy was thought, by superstitious minds, to presage the destruction of the empire, that happened immediately after, by that inundation of Goths, which spread itself all over Europe.

There are several other eruptions recorded, but not so considerable as the former, until 1631, when the earth shook so much as to endanger the total destruction of Naples and Benevento. This did inestimable damage to the neighbouring places; and it is computed near 10,000 lost their lives in the flames and ruins.

The air was infected with such noxious vapours that it caused a plague, which lasted a long time, and spread as far as the neighbourhood of Rome [now known to be bubonic plague]. Since which time, the most memorable are the eruptions in 1701, (of which Mr. Addison, who saw it, has left us a good description), and in 1717, as described above, by a curious spectator.

There have been eight eruptions within the last 30 years; of some of which Sir Wm. Hamilton has favoured the world with very particular and interesting accounts.

On the 11th, at night, I observed it from a terrace, at Naples, to throw up incessantly a vast body of fire, and great stones, to a surprising height.

On the 12th, in the morning, it darkened the sun with smoke and ashes, causing a sort of an eclipse. Horrid bellowings, on this and the foregoing day, were heard at Naples, whither part of the ashes also reached.

(165)

On the 13th we saw a pillar of black smoke shoot upright to a prodigious height.

On the 15th, in the morning, the court and walls of our house in Naples were covered with ashes. In the evening a flame appeared in the mountain through the clouds.

On the 17th, the smoke appeared much diminished, fat, and greasy. And

On the 18th, the whole appearance ended, the mountain remaining perfectly quiet.

To this memorable account it cannot be amiss to add, that the first notice we have of this volcano's casting out flames, was in the reign of the Emperor Titus. At which first eruption, we are informed, that it flowed with that vehemence, that it entirely overwhelmed and destroyed the two great cities Herculaneum and Pompeia [now usually called Pompeii], and very much damaged Naples itself, with its stones and ashes.

In 471, if we may credit tradition, this mountain broke out again so furiously, that its cinders and liquid fire were carried as far as Constantinople; which prodigy was thought, by superstitious minds, to presage the destruction of the empire, that happened immediately after, by that inundation of Goths, which spread itself all over Europe.

There are several other eruptions recorded, but not so considerable as the former, until 1631, when the earth shook so much as to endanger the total destruction of Naples and Benevento. This did inestimable damage to the neighbouring places; and it is computed near 10,000 lost their lives in the flames and ruins.

(166)

The air was infected with such noxious vapours that it caused a plague, which lasted a long time, and spread as far as the neighbourhood of Rome [now known to be bubonic plague]. Since which time, the most memorable are the eruptions in 1701, (of which Mr. Addison, who saw it, has left us a good description), and in 1717, as described above, by a curious spectator.

There have been eight eruptions within the last 30 years; of some of which Sir Wm. Hamilton has favoured the world with very particular and interesting accounts.

|

What tongue the dreadful

slaughter could disclose; |

|

Or, oh! what tears could answer half their woes? |

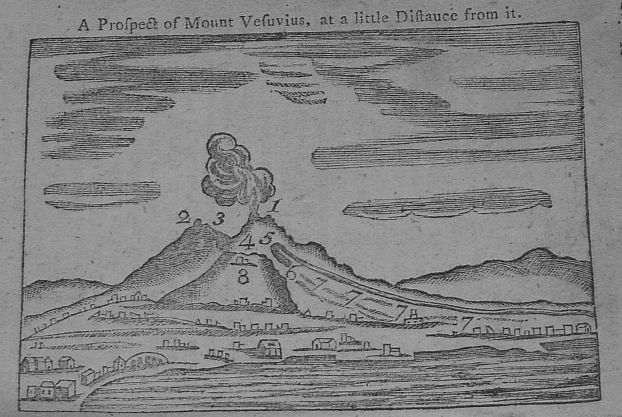

Explanation of the Cut of Mount Vesuvius.

- The Southern Summit, out of which the fire proceeds.

- The Northern Summit.

- The Rocks on the North.

- The Valley between the two Summits.

- The Opening on the Side where the fiery Torrent broke out.

- The first Opening, called the Plain.

- The Course which the last fiery Torrent took.

- The Chapel of St. Januarius.

HAVING been so particular in describing Vesuvius, we need say the less concerning ÆTNA, which is the greatest mountain in Sicily, eight

(167)

(168)

miles high, and sixty in compass. There are many of its furious eruptions recorded in history, some of which have proved very fatal to the neighbourhood; we shall instance only one, that began the 11th of March, 1669, and is thus described in the Philosophical Transactions [wikipedia.com states that this is a scientific journal published by the Royal Society; begun in 1665, it is the oldest scientific journal printed in the English-speaking world, and it is still being published], viz.

It broke out towards the evening, on the south-east side of the mountain, about twenty miles from the old mouth, and ten from the city of Catanea. The bellowing noise of the eruption was heard a hundred miles off, to which distance the ashes were also carried. The matter thrown out was a stream of metal and minerals, rendered liquid by the fierceness of the fire, which boiled up at the mouth like water at the head of a great river; and having run a little way, the extremity thereof began to crust and cruddle [obsolete term for "curdle"], turning into large porous stones, resembling cakes of burning sea-coal. These came rolling and tumbling one over another, bearing down any common building by their weight, and burning whatever was combustible. At First the progress of this inundation was at the pace of three miles in 24 hours, but afterwards scarcely a furlong [8th of a mile] in a day. It thus continued for fifteen or sixteen days together, running into the sea close by the walls of Catanea, and at length over the walls into the city, where it did no considerable damage, except to a convent, which it almost destroyed.

In its course it overwhelmed fourteen towns and villages, containing three or four thousand inhabitants; and it is very remarkable, that (during the whole time of this eruption, which was fifty-four days), neither sun nor stars appeared.

(169)

But though Catanea had at this time the good fortune to escape the threatened destruction, it was almost totally ruined in 1692 by an earthquake, one of the most terrible in all history. This was not only felt all over Sicily, but likewise in Naples and Malta. The shock was so violent, that the people could not stand on their legs, and those that lay on the ground were tossed from side to side, as if upon a rolling billow. The earth opened in several places, throwing up large quantities of water, and great numbers perished in their houses by the fall of rocks, rent from the mountains. The sea was violently agitated, and roared dreadfully. Mount Ætna threw up vast spires of flame, and the shock was attended with a noise exceeding the loudest claps of thunder. Fifty-four cities and towns, with an incredible number of villages, were destroyed, or greatly damaged; and it was computed, that near 60,000 people perished in different parts of the island, very few escaping the general and sudden destruction.

There have been ten other eruptions, one of which, subsequent to the preceding in 1753, was a very large one. Mr. Brydone, in his tour of Sicily and Malta, has given many ingenious particulars concerning it.

(170)

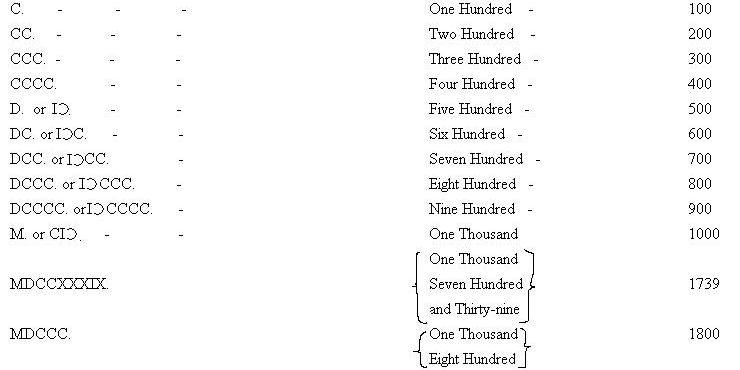

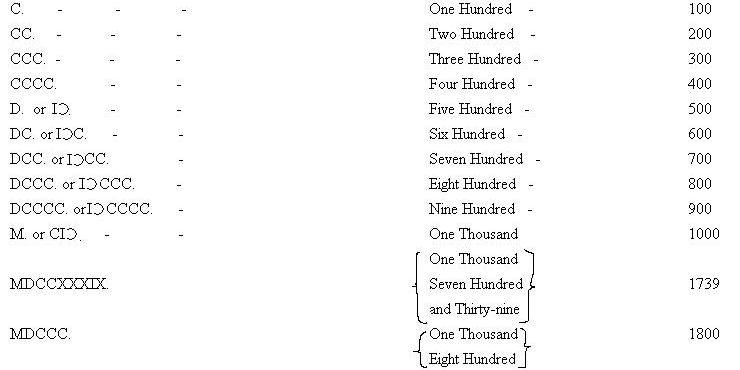

Explanation of NUMBERS expressed by Letters.

Explanation of NUMBERS expressed by Letters.

N.B. A less Numerical Letter, set before a greater, takes away from the greater so many as the letter stands for; but being set after the greater, adds so many to it as the letter stands for. --- For example, V stands for five alone, but put I before it, thus IV, and it stands for four; and put I on the other side, thus VI, and it stands for six. So X alone stands for ten, but put I before it, thus IX, and it stands for nine; and put I to it on the other side, thus XI, and it becomes eleven. So L stands for fifty; put X before it, thus XL, and it stands for forty, but put the X on the other side, thus LX, and it is sixty. So C stands for one hundred, place X before it, thus XC, and it is but ninety; again, put the X on the other side, thus CX, and it is one hundred and ten. So in all other cases.